Oct 5th 2025

If you don’t know what Igloo is please check out the Project Page.

This is not the best write up about Penguin, so I’d highly recommend you browse the GitHub.

Background

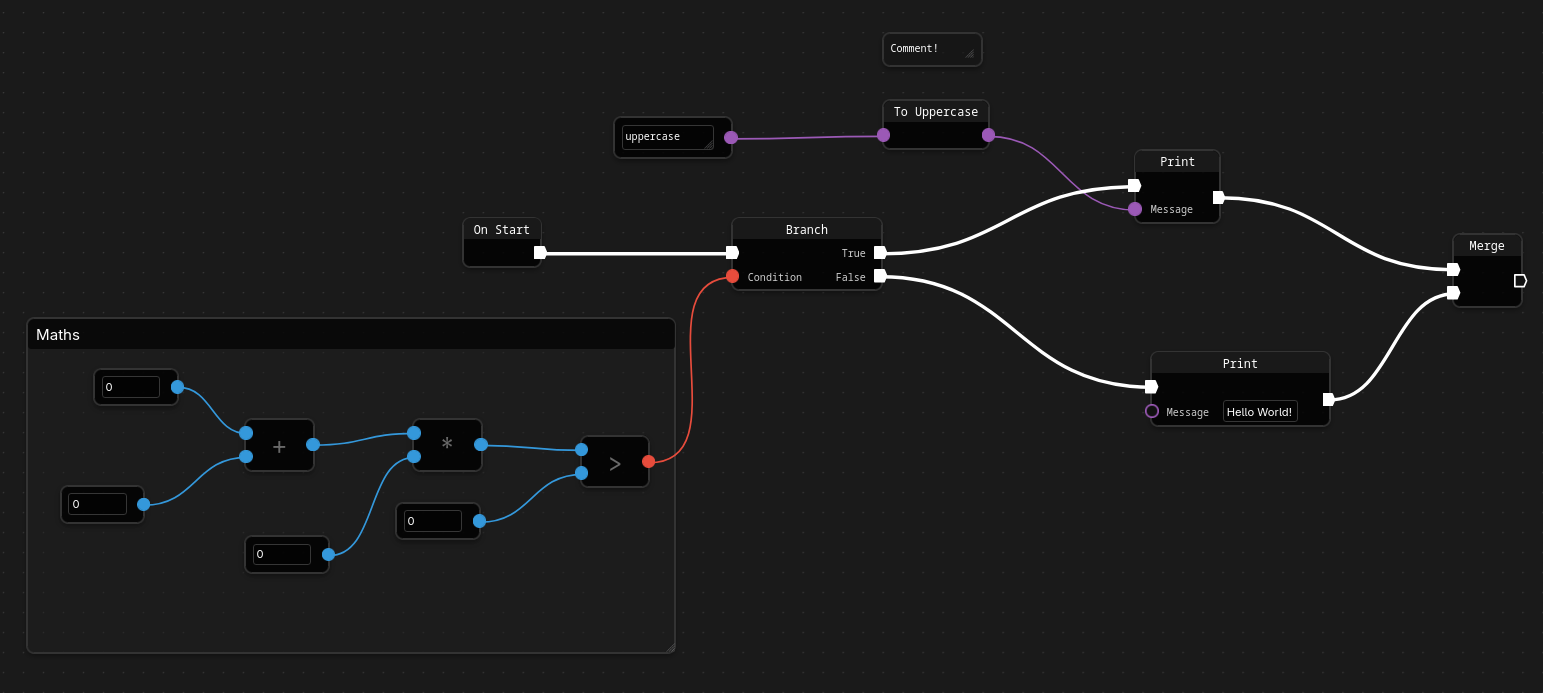

An essential piece of making Igloo powerful and intuitive, is making a good automation system. This is where Penguin comes in, it’s a visual node-based programming language that makes it possible for people to quickly and easily make their automations.

Block or Node Based

When I started I saw 3 clear ways to make Igloo:

- Block-based like Scratch and Blockly

- Node-based like Unreal Engine Blueprints, LabVIEW, n8n, and others

I chose node-based for two key reasons:

- Execution flow is much easier to follow in node-based, simply follow the white wire. In block-based it can be all of the place with different functions and long blocks for conditionals.

- n8n has shown a lot of success for creating automations and is loved among users who have minimal or no coding experience

What Makes a Good VPL

My experience with visual programming languages (VPLs) has been pretty mixed. I think that Unreal Engine Blueprints are great to work with, while LabVIEW is pretty horrible. The biggest thing I can point to as to why is the UX. Basically, having a fast and intuitive interface is fundamental to a good VPL.

While I do think the underlying language features are important, they can be completely ruined by a bad UX. This is why I have decided to spend so much time exploring different options and coming up with a really fast way to make a node-based editor in the web.

Failed Attempts

I have a directory on my computer of so many failed attempts at making Penguin. It’s lot harder to make fast than I thought. I ended up learning a lot about WASM and the limitations of reactive frameworks.

Why Reactive Frameworks Fail

I initially tried building Penguin in Dioxus and then Leptos. While both of these Rust web frameworks are very powerful and performant, they have big limitations on large graphs.

In Penguin each node can have 10-20 elements and each wire is 1 element. It’s very reasonable to expect a graph with 400 nodes with 1 or more wires connecting each of them.

The VDOM Diffing Wall

Dioxus’ Virtual DOM completely falls apart with this many elements. For every single update (ex. dragging nodes), we have to:

- Build a new virtual DOM

- Diff it against the previous frame (compare 4-8k elements + attrs)

- Compute minimal DOM updates

- Apply patches to real DOM

Dragging nodes around at 60fps is next to impossible.

Fighting Leptos

Leptos avoids a VDOM with fine-grained reactivity which makes it much faster than Dioxus, especially for this use case.

However, I found myself constantly fighting Leptos when trying to build out Penguin and apply all the optimizations needed.

The biggest problem I ran into was with wires. Wires need to be drawn from a pin on a node to another pin on a node. Since nodes and pins can both have different sizes, the only real approach we are left with is using getBoundingClientRect for each pin.

This operation is really expensive, so you have to minimize the amount of times you do it. The best way I found to do this is by measuring the pins offset inside the node and only updating it when needed. This way we don’t have to call this method for every frame we are dragging node(s). Doing this in Leptos means you need to build a ton of signals to connect between all these elements for ultimately worse performance than just doing everything in web-sys and wasm-bindgen directly.

Bevy

Taking a wildly different approach, I explored doing this in Bevy, a 2D and 3D game engine in Rust. While Bevy is an absolutely amazing tool, it just wasn’t the right fit for a few reasons:

- Bevy generates massive WASM files

- It’s really not made for this. Bevy 2D doesn’t really have support for exactly what I wanted to do. A lot of the features I wanted for laying out the editor and nodes use the UI libraries, which as of now, don’t support being placed in world space. This means it wouldn’t support panning and zooming.

wgpu

I very briefly explored doing this straight in wgpu. While this probably could have made the most efficient node-based editor, I realized that the amount of extra work required would not be worth it. Furthermore, I am by far no means an expert in shaders and I do not think I can come close to competing with the optimizations that browsers have.

Pure JS

As an experiment, I built out most of Penguin in pure JavaScript. This was surprisingly refreshing. It took very little time to come up with a performant solution that was under 1,000 lines. It served as a great reference for the final solution I came to.

A New Approach

The final approach I landed on was using web-sys, wasm-bindgen, and some JavaScript glue. It is nearly feature-complete and has exceptional performance, supporting over 10,000 nodes on my computer.

It has a lot of great features:

- Completely separates business logic from view logic

- Events start at the top (App) and are dispatches accordingly

- Strict visibility to prevent mistakes

- RAII: View structs (ex. Node, Wire, Pin) contain elements, observers, and closures that are automatically disconnected and removed upon Drop

- Custom element builder pattern

- Management of viewport transforms leveraging euclid

What This Looks Like

impl Wire {

pub fn new<T>(parent: &DomNode<T>, id: PenguinWireID, inner: PenguinWire) -> Self {

let svg = dom::svg()

.attr("class", "penguin-wire")

.remove_on_drop()

.mount(parent);

let border_path = dom::path()

.attr("class", "penguin-wire-border")

.stroke("transparent")

.stroke_width((inner.r#type.stroke_width() + 4) as f64)

.fill("none")

.event_target(EventTarget::Wire(id))

.listen_click()

.listen_dblclick()

.listen_contextmenu()

.mount(&svg);

let path = dom::path()

.attr("class", "penguin-wire-path")

.stroke(inner.r#type.stroke())

.stroke_width(inner.r#type.stroke_width() as f64)

.fill("none")

.mount(&svg);

Self {

inner,

svg,

path,

border_path,

from: WorldPoint::default(),

to: WorldPoint::default(),

}

}

pub fn redraw(&self) {

dom::js::redraw_wire(

&self.path.element,

Some(&self.border_path.element),

self.from.x,

self.from.y,

self.to.x,

self.to.y,

);

}

//...

}

This builder pattern makes this system super easy to use.

In just a few lines,

we set it up so when the user clicks on the border_path,

it will dispatch an event to App with the event target

set to it’s wire ID.

Now, we have a single entry point. App both holds a reference

to all view elements, the graph, the current mode, and events.

It can, for example, know to ignore hover events on pins, wires, and nodes

while you’re in dragging mode. Furthermore, it can track all changes

in history since it knows everything that happened.

Only Update When Needed

There are countless optimizations I’ve applied to reach the performance I did, so I’ll only talk about some of them here.

The most notable system is only updating things when they need to. This means:

- If we are dragging multiple nodes that have interconnected wires, we only need to transform the wires instead of redrawing them entirely

- We only need to find the BoundingClientRect of pins when the node resizes

- We don’t need a resize observer on every node (expensive) since we know it can only change size when wires are connected/disconnected from it

This is implemented through a dirty system. Basically all operations on the graph are done in cmds.rs. You can almost think of this as the byte-code for Penguin. It contains small atomic operations that can be combined into transactions.

For example, the add_wire method is a complex operation that can remove existing wires, add wires, and even add nodes. It builds a transaction of the these small operations and applies them.

When cmds.rs goes to apply these operations is tracks which nodes and wires

have been changed (are dirty) and then cleans them up after all operations

have been completed.

This has two big advantages:

1: Undo/redo system is very simple now. Each command in cmds.rs has an opposite/invert. To undo a command, you can simply just map AddNode → DeleteNode

2: Reduces # of DOM operations. If instead, we had immediately cleaned up nodes and wires, we would do useless work. For example, let’s say we want to move two nodes with a wire between them:

- Move node #1

- Update node #1 pin offsets

- Redraw wire

- Move node #2

- Update #2 pin offsets

- Redraw wire again

Now, in the dirty tracking system:

- Move node #1, mark node + wire dirty

- Move node #2, mark node + wire dirty

- Update pin offsets for dirty nodes

- Redraw dirty wire

Results

I’m super happy with the final solution. It’s performance while still being easy to read, follow, and add new features to.

What’s Next

Eventually I need to work on the Penguin executor, but before that’s possible, I have a lot more work to do on Igloo server. The next post will be following the development of the query engine.