liamsnow.com

Fast personal website made with Rust & Typst, hosted on Helios illumos.

Started:

2026-01-28

Ended:

2026-02-22

Language:

Rust

liamsnow.com is fast website written in Rust that has all content and layout written in Typst. There is no HTML, only Typst and SCSS.

Features

- Typst as a library with a custom world for blazingly fast build times

- Rayon parallel compilation (~10ms dev build time, ~130ms normally)

- Zero-copy responses via pre-compiled and compressed responses

- Hand rolled HTTP/1.1 server

- Hot reloading / watcher mode for development

- SCSS support

- Continuous deployment (GitHub webhooks trigger self-update)

Why Build This?

While many SSGs would work:

- I am very particular with what I want

- I want bleeding edge performance

- It needs to run on illumos

- I want to write everything in Typst

Why Typst?

For about a year in college I wrote all my notes in Obsidian. After so much frustration with Obsidian being slow, having to pay for syncing to mobile, and it being exceptionally hard to write extensions (at the time), I decided I needed something else.

I started just writing my notes in Markdown, using pandoc to compile it. I made a Neovim extension to automatically open up a browser preview of this. I experimented with writing all my notes in LaTeX, but it was just too tedious and time consuming.

Eventually I discovered Typst. It was the best of both worlds, the power of LaTeX (and more) with the ease of Markdown. It completely transformed my note taking experience.

When I was making the original version of my website, Typst HTML export was just not ready, so I set it up to use Markdown.

I used this for about half a year, but, I just always had this feeling that I had to do this in Typst. It would give me so much more power and make writing easier. Typst HTML export was in better state, but still not ready. It doesn’t have multi-page export and randomly breaks. However, I persevered through and was able to get it all working.

How it Works

Indexer

The indexer has two purposes:

- discover all files in the content directory

- read all files in memory

- grab Typst metadata

#metadata((title: "..", ..)) <page>

The first two parts are pretty simply, just recursively walk the file tree, then use Rayon to read all files in parallel.

The metadata part is where is gets tricky. If we want to use Typst introspection to get data from the page, we have to compile it. If we want to compile the file, we need to have all files already in memory, so it can properly read everything it imports without throwing an error. If we compiled during indexing, we would still have to recompile later, with the new inputs (Dict of its own metadata and potentially metadata from other pages).

This effectively doubles our compilation time. I tried a lot of ways to get around this and ultimately ended up on making my own Typst parser. Its extremely simple, with no evaluation or anything fancy – it just parses the metadata.

Compiler

The compiler’s goal is to take everything from the indexer and come up with a shared routing table that maps path → HTTP/1.1 responses.

Compiling Typst

With the index and metadata about all pages, we can form our inputs to the Typst compiler:

- The metadata for its own page

The metadata other pages it asked for. Ex.

blog.typasks for metadata forblog/*.typ.- We use a b-tree map formed by the indexer to quickly evaluate.

Typst doesn’t pretend to be meant to be used as a library. They publish many crates, but a lot of the implementation still lives in typst-cli which is not a library we can use. However, our life is a bit easier because we don’t need that many features. We can skip downloading packages, fonts, queries, watching, PDF output, etc.

Basically, you just create a “world” for the Typst compiler to use. This provides methods for it to find the standard library, source files, etc. Since we already have all our files loaded into memory, we can make our world extremely efficient.

The code for this is actually pretty simple. It was mostly just difficult to figure out what to do and required reading through a ton of source code.

Compiling SCSS

This was made super easy via grass. Grass is super cool because it lets us plug in our own file system provider. Just like in the Typst world, we already have files in memory, so we can just expose it like a virtual filesystem.

Compiling Responses

Now that we have all content compiled, the last step is generating HTTP responses. It’s pretty straight forward, but I have had a few features. Each response struct has:

- An identity (uncompressed) version

- A max quality Brotli version

- An ETag + 304 response for caching

HTTP Server

This ended up being a lot simpler than I thought. Since we already have all our responses generated, we only need a few things:

- Reading headers to find method, path, ETag, and Brotli support

- GET + HEAD handling

- TCP keep alive

- POST + body reading for GitHub webhooks

Hot Reloading

Having a hot reload system really helps with writing posts. So I set up a pretty simple system for this:

- Inject some code into the website which will connect to a websocket. When it recieves a message, refresh the page.

Watch for any file modifications in

content/(create, remove, modify)- Upon change, rebuild, then notify websockets

I couldn’t use typst watch for a few reasons:

- Typst doesn’t know about our dependencies from our custom query system

- We need to compile things besides just Typst files

Continuous Deployment

It would be really annoying if I had to SSH into my server, login to the zone, git pull, recompile, and restart the service for every change to my website. So, I created a pretty simple CD system.

I set up a GitHub webhook which POSTs to liamsnow.com/_update. Upon receiving this it will:

- Verify the sig/secret

- Git pull

- Recompile

- Stop the service (SMF will restart it)

Prefetch on Hover

I’ve always loved how fast and snappy McMaster-Carr is. So, I decided to bring over one of their best features – prefetching pages on hover. It prefetches pages when you hover over them, so that when you actually do navigate there, its already cached.

Results

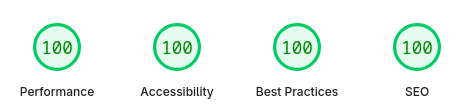

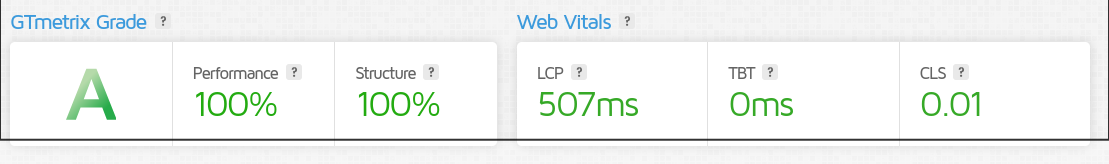

I’m super happy with the results. It’s fast, while having a great DX. I get to write posts in Typst, with hot reloading, and continuous deployment.